What's New in Nature?

Do you have something happening in your corner of Washington? - Please call a member or e-mail your observations to have them included here

This Month:

Typically, chicks do not leave their birth lake until just before it freezes. Biologists do not know exactly how the young loons know where to go—this is one of many mysteries. Chicks won’t return to their birth lake until they are approximately three or four years old, and they won’t be able to reproduce until they are six or seven.

Once they reach the ocean, the loons must adapt to life in salt water. Fortunately, loons have salt glands in their skull between their eyes that remove the salt from the water and fish they eat and excrete it from ducts in their beak. The ocean provides very clear, deep open water for the loons to dive and fish. They group together riding the waves and hunting in the shallow waters trapping schools of fish and filling their stomachs. In late-winter, their dull winter coat is replaced by a beautiful black and white breeding coat, replacing their worn out feathers with strong feathers to fly with, a process called ‘molting.’ Loons lose all their feathers at once, instead of losing one or two at a time like most birds, because they need a complete set of flight feathers to hold up their heavy bodies. During this approximately two- to three-week molting period, loons are unable to fly and are in great danger—they must expend a great deal of energy to grow new feathers and they have less energy to fight off illnesses or toxins stored in their body fat. Make no mistake—life on the ocean is not easy for these creatures. Loons must not only adjust to the stress of molting and a different diet, they must also endure the stress of rough coastal waters, stormy weather, marine pollution, and parasites.

Biologists suspect that loons return to the same general area where they were born, often returning to their very own birth lake. Loons will typically arrive on New Hampshire’s lakes and ponds just after ice-out, sometimes on the very next day!

March:

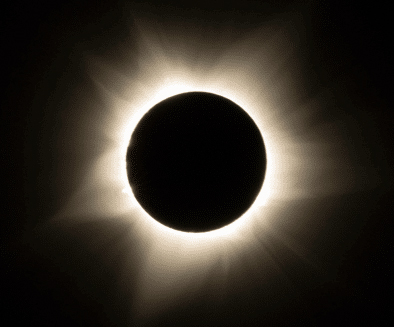

Although we won’t see totality here in Washington, the northern part of New Hampshire will. We will still see up to 95% coverage of the sun. The last time New Hampshire was in the direct path of a Solar Eclipse was in 1959, and the next won’t be until 2079. It will start here at around 2:15 pm, be at maximum coverage at 3:29 pm and the event will be over at 4:38 pm EDT

SAFETY is the number one priority when viewing a total solar eclipse. Be sure you're familiar with when you need to wear specialized eye protection designed for solar viewing by reviewing these safety guidelines:

1. Except during the brief total phase of a total solar eclipse, when the Moon completely blocks the Sun’s bright face, it is not safe to look directly at the Sun without specialized eye protection for solar viewing.

2. Viewing any part of the bright Sun through a camera lens, binoculars, or a telescope without a special-purpose solar filter secured over the front of the optics will instantly cause severe eye injury.

3. When watching the partial phases of the solar eclipse directly with your eyes, you must look through safe solar viewing glasses (“eclipse glasses”) or a safe handheld solar viewer at all times. Eclipse glasses are NOT regular sunglasses; regular sunglasses, no matter how dark, are not safe for viewing the Sun. Safe solar viewers are thousands of times darker and ought to comply with the ISO 12312-2 international standard.4. Always inspect your eclipse glasses or handheld viewer before use; if torn, scratched, or otherwise damaged, discard the device. Always supervise children using solar viewers.

5. Do NOT look at the Sun through a camera lens, telescope, binoculars, or any other optical device while wearing eclipse glasses or using a handheld solar viewer — the concentrated solar rays will burn through the filter and cause serious eye injury.

6. If you don’t have eclipse glasses or a handheld solar viewer, you can use an indirect viewing method. One way is to use a pinhole projector, which has a small opening (for example, a hole punched in an index card) and projects an image of the Sun onto a nearby surface. With the Sun at your back, you can then safely view the projected image. Do NOT look at the Sun through the pinhole!

Follow the safety guidelines and enjoy the show!

We have had sightings of Robins lately including one of a flock of hundreds of them together. Usually they appear later in the year as a sign of spring but we wondered - is it unusual to see American Robins in the middle of winter?

At AllAboutBirds.org (Cornell University) they get a lot of questions from people surprised by seeing American Robins in winter. But although some American Robins do migrate, many remain in the same place year-round. Over the past 10 years, robins have been reported in January in every U.S. state, except Hawaii and in all of the southern provinces of Canada.

As with many birds, the wintering range of American Robins is affected by weather and natural food supply, but as long as food is available, these birds are able to do well for themselves by staying up north.

One reason why they seem to disappear every winter is that their behavior changes. In winter robins form nomadic flocks, which can consist of hundreds to thousands of birds. Usually these flocks appear where there are plentiful fruits on trees and shrubs, such as crabapples, hawthorns, holly, juniper, and others.

When spring rolls around, these flocks split up. Suddenly we start seeing American Robins yanking worms out of our yards again, and it’s easy to assume they’ve “returned” from migration. But what we’re seeing is the switch from being nonterritorial in the winter time to aggressively defending a territory in advance of courting and raising chicks. This behavioral switch is quite common in birds.

This information found at AllAboutBirds.org

The Granite State may have been pummeled by a good old snowstorm on Sunday, but the 50-degree temperatures, rain, and flooding emergencies that followed a few days later were quick reminders that winters here are changing.

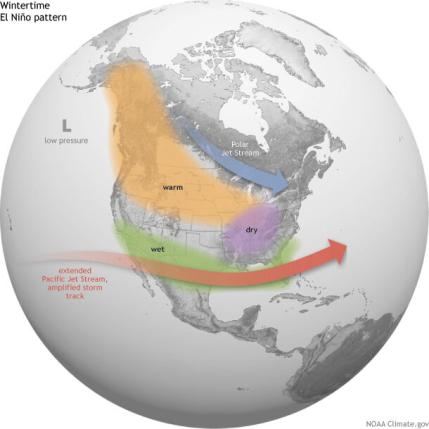

This year specifically has a unique fusion of factors: an El Niño weather pattern combining with the effects of climate change, said state climatologist and University of New Hampshire associate professor of geography Mary Stampone, causing “an enhanced warming this winter.”

El Niño and La Niña are two opposing natural climate phenomena that break from normal conditions, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The two contradicting patterns can impact everything from seasonal rains in Africa, to monsoons in Asia, to New England winters.

Trade winds are weak during El Niño and strong during La Niña, ultimately influencing “hemispheric-scale seasonal weather,” Stampone said. While their impacts fluctuate and vary based on geographic location, in northern New England, El Niño is historically associated with warming and La Niña with cold.

“During El Niño, you end up having a warmer water pool off the coast of South America, and that then influences atmospheric patterns across much of the northern hemisphere,” Stampone said.

An El Niño winter is occurring for the first time in four years, and NOAA first declared its arrival in June.

As a result, the agency’s U.S. Winter Outlook predicted warmer-than-average temperatures across the northern tier of the U.S. and much of the West, noting that northern New England is among the areas with the greatest odds for such conditions.

In fact, NOAA’s blog providing updates on El Niño posted in December about a 54 percent chance this El Niño event will end up “historically strong,” potentially ranking in the top 5 on record.

Neutral conditions are expected to return between April and June.